We know now that an outdoor tool cabinet was probably a bad idea. Upside, we have a full drawer of chicken feathers and seeds if you need any.

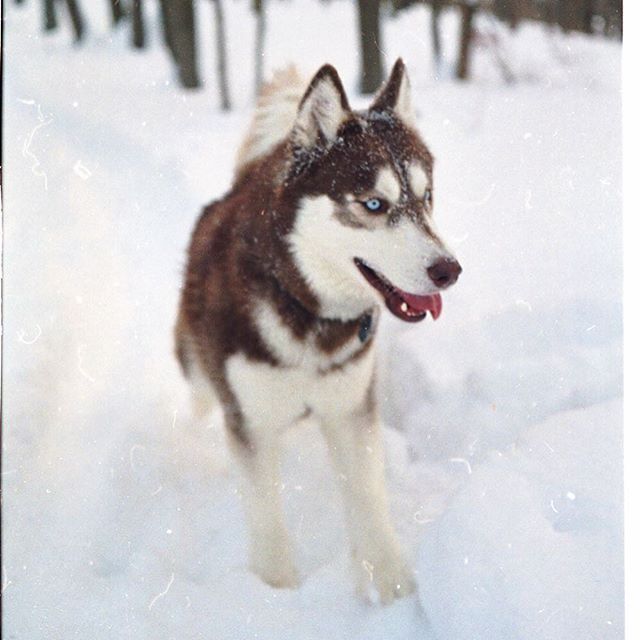

2019 Arctic Heart Expedition: Part Four

Life & Death

A caribou taken during a spring hunt in the Brooks Range.

Robert Thompson hauls two caribou behind a snowmachine.

Jaw bones from a Bowhead Whale on the coast of the Beaufort Sea.

On our first morning in the Arctic, Charly wakes me up early. He leans in the door of my room in his long johns and non-chalantly asks “Wanna see a polar bear?” F@$% yes, I do.

From the kitchen window he points to a cream colored dot moving across the sea ice at the edge of town. I throw on winter clothes, grab a camera with a long lens, and head outside. I have gone from fast asleep to absolutely wide awake in seconds. Seeing a polar bear has been a dream since I was small. From a snow bank on the edge of town I spot the bear laying near the tall wooden snow fence that slows the wind from the east. I snap several frames, wonder about moving closer for a better shot. But before I can fold the legs on the tripod, a snowmobile approaches the bear. Polar Bear Patrol. They are tasked with keeping bears away from town, trying to prevent the increasing likelihood of negative interactions between people and bears as deteriorating sea ice conditions push more of these arctic giants onto land.

Patrol fires a bean bag that startles the bear. He rises and initially starts towards where I’m standing. My right hand goes automatically to the handle of the pistol on my belt, my fingers brushing the grip just to check that it’s there. The other keeps training the camera on the moving bear. The patrol member pursues the bear on a snowmachine, turning him out and away from town toward the barrier islands that separate Kaktovik’s lagoons from the open ocean. The bear disappears beyond the gravel bar into the jumbled, broken ice of the Beaufort Sea. I’m elated.

Day two in the Arctic and I’ve seen a polar bear. Albeit at a large distance. But I got a quick glimpse and somewhere at the end of those tracks is a bear. That’s a place to start. This simple sighting, a relatively common occurrence for those who live here, is the fulfillment of a childhood dream for me. A polar bear in the wild. Among other tasks that day we find time to walk out on the ice, find tracks before they drift in, fresh scat. I take bearings and triangulate a position on my map.

Polar bear tracks in the snow near Kaktovik, Alaska.

The next morning I wake on my own. 4:45 am. I dress and head outside; start walking toward where I can pick up tracks from the day before. Before I even get to the mark on my map, I cut a fresh line of paw prints in the snow. Even with a dusting of new flakes and a breeze they haven’t drifted in. These are fresh, less than an hour old by my guess. I follow them back across the sea ice, back to the corner of town. They lead between two buildings and up to the front steps of a small house. And there in the front yard is a man skinning a polar bear. My heart drops.

I try to hide the disappointment on my face. I say hello and ask if I can join him for a little while.

George is gracious and invites me to touch the bear, to watch what he’s doing. I pull off my mittens and kneel in the snow. The bear is still warm, his ears impossibly soft between my fingers. I roll back his thick rubber lips, slide my fingers over his teeth, smell the last fading whisper of his breath. I am trying not to cry.

George is working with a traditional ulu, turning the thick, dark hide back and away from the flesh. Knuckling out the massive paws to keep the huge arching claws attached to the skin. Carefully parsing the tissue that holds the ears to the skull. His wife, Reeanin (this may be a misspelling of her name, if it is I apologize) joins him, working side by side in the early, warm light of the morning. I ask if I can take photos and they both say okay.

They roll the bear to it’s side, slide the knife along the bone and separate the hip at the joint. It’s a young male—three, maybe four years old, and a little more than 8 feet long. While they work George tells me that this bear has been spending more and more time in Kaktovik, particularly here in his yard where town meets the sea. Reeanin tells about the dog it mauled a few weeks ago that miraculously survived after being flown out to the vet. George talks about stepping out to walk their daughters to school and being surprised by the bear laying in their yard when they rounded the corner of the house. This morning, the bear coming up his front steps—exploring the door of their home—is the last straw. He opened the kitchen window and shot it at close range, knocking it down. I realize his gunshot is likely what woke me up.

I can tell he’s choosing his words and stories carefully, gauging my response. He’s waiting now to see how I’ll react. I tell him I understand; tell him honestly that I would do the exact same thing. I try to imagine what it means to be have a bear at the door with small children in the house. I lift the edge of my parka and show him the Smith & Wesson .44 loaded with high-grain hard-cast rounds that I’m carrying in case something exactly like this happens to me. He seems relieved that I’m not upset with him.

George has a right to take a bear if he wants to, and not just in self defense. Provisions under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the law that governs the hunting of polar bears, allow for harvest by Alaskan Coastal Natives. But George makes a point to say that this wasn’t hunting. This was done out of necessity. A bear that’s too comfortable around people is dangerous. George and Reeanin have little kids. Something had to be done.

I agree with all this, but there is still grief resting like a stone in the pit of my stomach. A graceful, wild light has been put out. I understand that this is the way of things here. The Arctic is a place where life and death are always walking side by side—wherever you find one, the other is close at hand. This is true in many wild places, but even more so in the far north where human interference has not blunted the knife edge on which survival balances. From top to bottom the food chain is intact; a powerful, beautiful magic that is still often bloody and brutal to observe. And people, though dominant here as they are everywhere around the globe, are not as far removed from that chain as they are in lots of the modern world. Subsistence hunting is a very real part of life in this place and big predators are sometimes taken in legitimate acts of self defense. I know this. But I still can’t set aside a feeling of loss.

I snap a few more photos, thank them for their time, and spend the next half hour walking around town alone. I’ve just taken what will be, to me anyway, the most striking images of my trip, but they’re of something I never wanted to see. What do you do with that? I’m both disappointed in the outcome and humbled to have been there to see it. As a photographer I’m sad to know that the bear I was tracking—along with the chance to get more photos of him alive—is gone, but relieved as a person that no one has been hurt. I’m still trying to sort out exactly how I feel about all of it.

But here’s what I know to be true: polar bears aren’t declining on the Beaufort Sea because George had to shoot one at his door. Polar bears are declining on the Beaufort Sea because millions of people in the United States drive SUVs to soccer practice. That’s obviously a vast over simplification, but you get the point.

It would be easy to blame George, instead—to blame other coastal natives who have harvested polar bear, sometimes in self defense, sometimes as part of a hunting tradition that dates back to the earliest human inhabitants of this continent. I’ve been reluctant to share this set of images for exactly that reason—struggled with how to go about telling a story that is only partly mine because I see how easily it could be misused, misinterpreted. My fear is that someone will paint George as the villain. He is not. I hope, instead, that you see the complicated truth: we are all to blame.

Our failure to address climate change in any meaningful way is causing unprecedented changes in the Arctic—changes that are forcing bears onto land, away from their preferred food sources, and drastically increasing the likelihood of negative interactions with people. That’s our fault. Plain and simple. Much like my previous posts, I’m not trying to point fingers here; my actions contribute to the problem too. But I also want to talk about solutions. Putting our heads in the sand is not a viable option anymore.

The problem is admittedly daunting. And while I won’t pretend to have all the answers, I know that they lie in working with the rest of the world, not against it. The United States needs to return to climate discussions, and not just as a silent sulking presence in the corner. We need to take a leadership role, one befitting of our out-sized role in causing the problem. To do that we need to push aside any politician (would-be or incumbent) who is too dim to understand or too arrogant to recognize the enormous body of scientific evidence outlining the perils of a changing climate and our role in causing it.

Now as time and distance soften the memory of that morning, I’m trying to hold on to that bear; an enduring image of what is at stake if we fail. I bury my bare hand in his coat, his body still warm against my palm. I commit to memory the weight of his massive paw, turn it up with both my hands to see the black pad ringed in brilliant white fur. Brush the ice back from his muzzle where his last breath froze. This is why. This. Remember this. And do everything you can.

2019 Arctic Heart Expedition: Part Three

A Big Land

From Kaktovik we traveled west over land-fast sea ice to the mouth of the Hula-Hula River, then up river across the coastal plain, past the Saddlerochit Mountains and into the foothills of the Brooks Range. Rivers are the highway system of the Arctic. We traveled on the river ice as much as possible, but in a few places water moving over the ice forced us onto land, into the hills, bouncing over frozen tussocks and gravel bars to get back to the next section of good ice. It's rough country.

Two slow, grinding days put us at the place where Old Woman Creek and Old Man Creek meet the Hula Hula River, like perfectly opposite branches on a child's drawing of a tree they reach east and west through the foothills of the mountains. A beautiful spot but still twenty-some miles short of our intended destination at the Schrader Lakes. We set camp in a willow thicket that would be home for the next 6 days.

"This is a land big enough to hide 150,000 caribou," says Robert Thompson, as we pause on the striking, epic flat of the coastal plain. The jagged broken teeth of the Brooks Range punctuated the horizon. The scale of the north slope is incredible. It is immense. And Robert is right. This land is home to the Porcupine Caribou Herd, now estimated at 190,000 animals strong, and there are times when no one knows exactly where they all are.

To be clear, somebody always knows where some of them are. There are radio collared caribou; someone is keeping track. But the herd doesn't necessarily stay together as one contiguous group, in fact they rarely do. Like the rivers here that so easily slip the bonds of their banks and braid their way across the land, the caribou flow from mountain pass to coastal plain and back again, splitting and rejoining their course seemingly at random, constantly moving. Even their mass migration to the calving grounds on the coastal plain is notoriously hard to predict. Over the years, many scientists, photographers, and sight-seers have tried (sometimes at great effort and expense) to plant themselves in front of the oncoming herd and failed.

Despite what the oil companies would have you believe, the coastal plain is absolutely teeming with life. It is not the barren wasteland portrayed to congress by lobbyists and liars, many of whom have never even set foot on the coastal plain. The Gwich’in call it the sacred place from which life comes. In his book "Being Caribou" Karsten Heuer describes the magic of such abundant life as a "thrumming," an almost audible life force constantly surrounding you. Even in April when food is relatively scarce, the snow is webbed with tracks, the coming and going of so many living things drawn one on top of the other in the snow. Ptarmigan. Fox and wolf and wolverine. Caribou and sheep and moose. Grizzly bears. But even impressively big animals are not so easy to find in a massive land.

I'll admit that I am fairly disappointed with the wildlife photos I was able to get during my time in the Arctic. A tiny white dot in a white landscape, the mighty polar bear. A tiny red dot in a white landscape, the sly red fox. A small brown sphere in a white landscape, the elusive shrew. Ptarmigan are everywhere. But there are only so many ptarmigan photos you can take; white dots in a white landscape.

"It's not like the BBC," says Nancy Pfieffer, long-time Alaska resident, author, and wilderness guide. "Clients think they're going to see a pack of wolves taking down a caribou. They don't realize you could spend your whole life up here and never see something like that." I nod along as she says this. Of course. I know what she’s saying is true—knew it well before I even started planning for this trip. But if I'm being completely honest, deep down that's still exactly what I was hoping to see. Or at least something like it: a polar bear with two infant cubs, caribou walking along a ridge top outlined in midnight alpenglow, an arctic fox pouncing into sparkling snow after ground squirrels. I think that's what every photographer is hoping to catch. And I know not everyone gets one of those photos, but somebody gets it, right? Why couldn't it be me?

They say the universe gives you what you need, even if it's not always what you want. It would seem the Arctic vehemently believes that I need more humility, because that's the lesson it handed over and over. On this trip we went from plan A, to plan B, to C and D, and eventually arrived at living in the moment instead. We watched as mechanical issues, and weather, and changing ice shifted our path and plans. In the last days of the trip more water moving over the river ice (fast moving and more than a 18 inches deep in places) would turn us back from reaching another camp and send us back across the coastal plain a day early to avoid more difficult river crossings as more water came down stream. The best laid plans of mice and men, I suppose. It was hard—for me anyway—to let go of thinking we had control. But, in the end, I think that’s exactly why we need wild places.

By definition, wilderness is a place outside of our control. A truly wild place does what it does; keeps doing what it has always done, regardless of our presence. Cycles of life and death continue on uninterrupted by our meddling. We can not cue the caribou and polar bears, tell them when to enter stage left and give us a show. That’s part of the magic: the clear reminder that we are not, in fact, the center of the universe. When we put our mark on the land—bend it to our will—we change that balance and the essence of wilderness is gone. It becomes something else. And while that new thing may still be beautiful and interesting it is fundamentally changed. Something is irreplaceable lost.

So, this is what I keep coming back to: the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is still truly wild and we can keep it that way. It belongs to us collectively as a nation, a treasure held in common. The Refuge—and this is true for many of our other public lands—was not set aside for future generations to destroy. It was set aside to preserve in perpetuity. It is a place to keep safe, not just for our generation or maybe the next, but for all generations—for all people. It’s a place to see the wild beating heart of this continent, press your hand firmly against it, and feel a pulse. Places like that are increasingly rare. It’s our job—our moral obligation, even—to be good stewards, to pass down something unharmed for our children and the generations to follow. For a long time that concept of stewardship has been part of our national character, part of what it means to be an American. I was raised to believe in a United States that was strong enough to protect and preserve its lands. Have we really become so weak—so desperate and afraid—that we would allow the destruction of every last corner of this great land for the profit of a few? What happened to the home of the brave? I, for one, still believe in a United States that doesn’t bend to cowardice and greed. I believe in an American people who can stand tall and proudly defend our lands from those who would ruin them.

Join me in reminding our politicians that our public lands are not for sale, that we, the owners of those lands, are not considering offers—now or ever. One way to do that right now is to let your representative and senators know that you expect them to support the Arctic Cultural and Coastal Plain Protection Act. HR1146 already has 179 co-sponsors in the House and is waiting for introduction to the Senate. This is something easy we can do to protect the future of the refuge and the future of the Arctic as it is today.

2019 Arctic Heart Expedition: Part Two

Traveling south into the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge on the Hula Hula River.

Snowmachines

I hate snow machines. Always have. They're loud. They reek of two-cycle. They chase away wildlife. And most of all, they tend to break down at precisely the most inconvenient times. BUT they can give you access to places that would otherwise be out of reach for a two week trip. With no roads in or out and snow cover from September until May, they are the obvious mode of transport in Kaktovik. Simply put, they are part of life in the far north.

And so, just like any farm to do list in Wisconsin begins with "Fix Tractor," any trip in the arctic begins with "Fix Snow Machine." I'm not a mechanic. Working on recoil starts and clutches and engines was among the most frustrating things I've done in a long time. At one point, I asked Roland—a friend of our host who was helping us get machines in order for our trip—if there was some trick to getting these started, something I was missing. He looked at me, red-faced and sweating through my jacket from hauling on the pull start over an over, looked down at the yellow ski-doo sitting dead in the snow between us, and said, "The trick is...you have to pull it until it starts," nodded and then walked away. Fair enough.

Craig and Charly adjust the tow line for one of the sleds carrying food and gear.

I'm proud to report that in the end, we met with at least marginal success. Enough anyway (along with a newer rented machine that would later break down as well), to get our group, our gear, and plenty of food out of town and into the backcountry, each machine towing a sled loaded with tents, food, fuel, and gear all wrapped up in a canvas tarp. Each sled also carried a rider who helped to keep the load tracked out straight behind the machine as we crossed the most rugged land I've ever seen.

From Kaktovik, we went west. Across land-fast sea ice and frozen lagoons to the mouth of the Hula Hula River and then turned, following the path of the river south across the coastal plain toward the Sadlerochit Mountains and the northern edge of the Brooks Range. We would ultimately spend 8 nights in the field, leaving a day earlier than planned as changing ice conditions on the river made travel increasingly difficult.

Now, at this point it’s important to note that the irony of using snow machines for this trip is not lost on me. To go see a far away place threatened by oil development via gas powered transportation is admittedly complicated. I get it. Each time I saw the cloud of blue exhaust that comes out of a cold engine when you first fire it up, I felt like a complete hypocrite. I felt the same way watching our plane refuel on the runway in Seattle. We are dependent on fossil fuel. That's a fact. And I'm not just pointing fingers at everyone else, we’re all in the same boat.

Aufeis or overflow is early spring melt that moves over the top of the frozen river, wetting the snow and creating a striking blue layer of ice when it freezes overnight.

But here's the thing: I'm not saying we should never use fossil fuels. If we woke up tomorrow and decided not to use another drop of oil, we'd be totally f@#$%. Totally. We need to transition to alternative energy, ween ourselves off—a process that we've barely started and requires the continued use of some oil. It's going to take decades to complete that process and even then there may be smart uses of fossil fuel even into the far distant future. In the mean time, we need to use the resources we have judiciously.

Fortunately for the Arctic Refuge, there are other sources of these fossil fuels that don't require the whole sale destruction of the coastal plain. In fact, even inflated estimates of the oil reserves within the contested 1002 region aren't especially large compared to known reserves elsewhere in the United States, places already disrupted by development. The end product of drilling in the Refuge would represent only a tiny fraction of our national oil needs. Not to mention the US is actually exporting oil as we speak. In short, I don't want to hear a single peep from anyone wrapping themselves in our flag and claiming that this oil contributes to our independence. We don't need to choose between the Arctic Refuge and independence; we can easily have both.

Harvesting arctic oil comes at a high cost, namely the loss of this wilderness—one of the very few fully intact wild ecosystem in the US. From its apex predators down to it's smallest life forms, the arctic is still a complete system. A land intricately balanced. That's something we can't replace, no matter how much money or popular support we have. Once its gone, it's truly gone. But here’s the thing: we can simply choose not to destroy it—we have that power.

Big oil would have you believe that they can add major infrastructure to this land and not tip that balance. They are either hopelessly arrogant or tragically dim. Maybe both. Anyone who has seen Prudhoe Bay can tell you that oil extraction is not light on the land, or the native people who have lived there for countless generations. Seismic testing, drill platforms, militarized security protocols, and pipelines disrupt the natural rhythms of life and land in staggering ways, many of which we're still discovering.

So, long story short, why risk it? We have this wild and beautiful thing, this Refuge that belongs to all of us. And yes, it does contain a small amount of oil, but we don't actually need it. So let's just leave it alone. Keep this piece of wild intact. Seems like simple math to me. And here’s where you come in: tell your elected officials the same. Even if they don’t agree; maybe especially if they don’t agree. Tell everyone. We only get one shot at this. Make it count.

Frost on the Hula Hula River.

2019 Arctic Heart Expedition: Part One

View of the Brooks Range from the Ravn Air flight from Fairbanks to Kaktovik, Alaska.

Getting to the Arctic

"Barter Island, as promised," says the pilot, climbing out from behind the controls and dropping the side door down to the gravel runway. In lieu of an airport, a small blue bus is pulling onto the runway to meet us.

"A promise easily broken," says Jennifer Reed in a quiet, dry tone. Reed is the Public Use Manager for the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and by chance one of the passengers on our eight-seat flight to Kaktovik (sometimes written Qaaktugvik), the small coastal village on Barter Island. A frequent traveler here, she's joined on this trip by Refuge Manager Steve Berendzen, Park Ranger Will Wiese, and another independent contractor. As we cleared the mountain rampart of the Brooks Range and soared over the coastal plain she was marking edits in the US Fish and Wildlife Polar Bear Source Book—a document I read in full no less than three times in preparation for this trip. I am curious to know her changes, but too shy to ask.

Many flights to these remote northern airstrips are delayed or diverted due to inclement weather. High winds, fog, snow. All three. Here, the driver of that rough weather is the Beaufort Sea. Weather rolls in from this marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean and, with virtually no change in elevation from sea ice to tundra, batters the settlements on this northern coast.

On our departing flight two weeks later we would stop to pickup another passenger at Fort Yukon, where a cross-wind would force a skewed approach to the runway and some quick last minute maneuvers. This was all deftly executed by two pilots who appeared to be younger than several of the clothing items I packed for this trip. I doubt our landing would even stand out as unique to them—I'm certain they have flown in far worse—but after bumping down the runway and stopping in front of the pole building that serves as a terminal, Charly would look across the narrow aisle with eyebrows slightly raised and say, "well, that was sporty."

A small bus meets planes at the airstrip in Kaktovik

A long spring sunset in Kaktovik, 11 pm.

Sign at the edge of town which includes an alternate spelling: Qaaktugvik

A snow bunting perches on a shipping container in Kaktovik

All this to point out, that just getting to and from the Arctic is not super easy. To be clear, it's markedly better than the days of Franklin's Lost Expedition, but it's still safe to say its the edge of the map. I'm not being hyperbolic; Kaktovik is literally the far northern edge of the continent. On most maps (when marked) it's followed by a little blue area labeled "Beaufort Sea," and then the margin.

Therein lies one of the biggest challenges to protecting this place from the greedy, wandering eyes of big oil: almost no one goes there. And, realistically, that's not going to change. In some ways, that may actually be its best defense. But how do you give people a connection to a place they've never been, and probably never will? How do you convince a weary public that such a place, held in trust for the people of this great nation, has value beyond the tiny supply of fossil fuel hidden beneath the fragile skin of the tundra?

Overflow ice on the Hula Hula River looking from the Coastal Plain toward the mountains of the Brooks Range.

My hope is that my photos can help, that they can give you a vision of a land you may never see and convince you of its value as an untouched wilderness rather than oil field. These images are not the first of their kind or the best, but they do represent one more piece in the body of evidence that supports the Arctic Refuge's claim as one of America's few remaining patches of true wilderness—a distinction that once destroyed can never be rebuilt. Now is our chance to preserve this wild and rugged land, to pass it on unharmed for future generations.

The immense open land of the coastal plain in the contested 1002 area of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Super Moon Eclipse -PRINT SALE!

Still want a copy of that sweet Super Moon Eclipse Photo? You're in luck! There are two sizes to pick from (10"w x 4"h or 30"w x 10"h) and they're both on sale until Friday at midnight.

Don't see the size you want, give me a shout here and let me know what you're looking for.

Henry's House of Coffee-San Francisco

Happy National Coffee Day, everyone. And to celebrate, I'm sharing some photos from my trip to Henry's House of Coffee in San Francisco this past April.

I love traveling. Love it. Add in a photo shoot and I love it even more. Add hand roasted coffee and I'm pretty much in heaven. So, when friend and fellow designer Mike Sterner asked if I could hop a plane to San Francisco to get photos for Henry's House of Coffee, I jumped.

April was a busy month and the trip ended up being a really quick endeavor: fly in Tuesday evening, shoot all day Wednesday, then catch the red-eye home and wind up back in Wisconsin early Thursday morning– a bit of a whirlwind. But the shoot was amazing. And so was the coffee.

I've been a firm believer in coffee for a long time. I would even consider myself devout. But to be honest I didn't know that much about it, except for the simple truth that it makes me bearable to anyone that has to talk to me before noon. (Thank you, coffee; we are all grateful). Over the course of our shoot, Henry and his son, Hrag, gave me a crash course in coffee, and I seriously should have taken notes. We talked about everything from roasts to flavor profiles to the origins of different beans. I was even treated to a cupping of three of their coffees to compare. It was simply amazing.

But even more than the education in coffee, it was amazing to watch them at work. One of the things I love about assignment photography is getting to watch someone do what they do best. You never fly across the country to take pictures of someone who's mediocre at what they do, right? You go to see someone who's great, someone at the absolute top of their game.

Coffee roasting is a family tradition for the Kalebjians. Henry and Hrag are second- and third-generation roasters. They are masters of their craft. And, for a photographer, it doesn't hurt that the tools of their trade are pretty photogenic, too. The back room is filled with burlap bags and wooden barrels of green coffee from around the world. The walls are lined with handmade shelves filled with tins of freshly roasted coffee in every tone from lightest tan to the richest chocolate black.

And then there's the roaster. Planted right in the corner of their Noriega St. shop for all the world to see, it looks like something out of the 1800's: all black steel and brass knobs with a round glass portal into the roasting drum and a green enamel cooling pan.

To watch Henry at the helm of that magical machine is to watch an artist at work. He's constantly checking the sampling tube, smelling the roasting beans, listening for the "first crack"–the sound that indicates a change in the roasting beans. All with stopwatch in hand, tracking the minute details of each batch for his records. And at the precise moment, the hatch is lifted and Henry disappears in a blue swirl of smoke and steam as the beans tumble out into the cooling pan, stirred by mechanical arms as they come down to room temperature. Let me tell you, the smell in that room is absolutely incredible.

Great coffee, great photos, great trip.

Freshly roasted beans cool before being transferred to storage tins.

Single-estate Wallenford Jamaican Blue Mountain beans.

Harvest Series

Sometime last week, there was a shift; a subtle, nearly imperceptible change. I can't say precisely when. But it happened. It definitely happened. One night (maybe Tuesday; it's really hard to tell) without great fanfare and witnessed only by the stars, summer softly became fall.

And now it's the season of harvest. The season of gathering back in all the hope of spring and canning it for winter. The season of collecting seeds and putting roots in the dry darkness of the cellar. The season of splitting wood.

To celebrate that season, I'm working on a new series of photos called Harvest. They are simple and clean, the plentiful symbols of the season on display. Stay tuned for more new images and a post on how they were shot. And watch for prints and greeting cards from the Harvest Series to be available soon in the HLP Gallery and Store.

Camping (And A Brief Discourse on the Origins of Humankind)

I usually think of camping as this thing that I do when I go somewhere else. Glacier National Park: camping. The Bad Lands: camping. The remote foothills of the Andes Mountains: camping. As a result, when I don't travel–when I don't go somewhere far away–I don't go camping. But that means I don't get to go camping that often anymore. And I miss it. I miss how simple it is.

This year, to celebrate my birthday, Sarah planned a camping trip pretty much right outside our back door. Four miles from our house to be exact, at a little lake in the Chequamegon Nicolet National Forest. At first it felt a little silly packing up all our things to go just down the road, but once we pulled off the paved road and claimed the little site along the lake shore where we planned to stay, the rest of the world fell away. And we were camping.

The thing I like about camping is moving slow. Nothing is a rush. You rest when you're tired, you eat when you're hungry. You walk, you paddle. You stare quietly into the glowing coals of a dying fire that's just barely holding the darkness at bay. You wonder at the myriad of stars. And all of it, every little part, ties us back to our past. Not our little individual past, but the vast expanse of past that we all share. Our past.

Over the last 100 years, harnessing and honing the power of the internal combustion engine, we have traveled at an ever increasing rate, eventually breaking the sound barrier in our pursuit of speed. But for roughly 195,000 years preceding that human beings traveled at something like 3 miles per hour pretty much all the time.

Three miles per hour. Think about that. We walked, 3 miles per hour. We paddled, 3 miles per hour. Riding horses entered into common usage something like 4000 years ago in certain parts of the world (much later in others) and even then, that only increased our pace to roughly 5 miles per hour for any significant distance. We moved slow. And anywhere that we traveled we felt the earth under our feet and the movement of the water that carried us. We actually touched every place that we went. Not figuratively, but literally touched it; skin to earth. And at that modest pace we stepped out of Eastern Africa and walked around the world. That's our story as the people of Earth.

We walked north into Asia, turned in opposite directions, and at 3 miles per hour, over the wandering course of generations, we circumnavigated the globe. And when we finally met on the other side of the world, we couldn't recognize each other anymore. So, we fought– we still fight– not remembering that we all started this walk together. How bizarre.

But camping, in its own simple way, brings us back to the people we were at the beginning. Reminds us that we all walked here together; that we all sat at this fire and stared at these coals, deciding which way we should walk tomorrow. I like that. Thanks, Sarah, for reminding me.

Instagram.

Well, I did it. I joined Instagram. Astute readers and close friends will realize this also means I finally got a smart phone. Yes. True story. No worries though, my number is still precisely the same. I fought this smart phone thing for a while, but you know what? It's actually kind of cool. And so is instagram (except that I really don't understand why so many people are posting photos of their nail polish...it's nail polish...I don't get it... are we supposed to be seeing something special about the nail polish...am I missing something?...I'm confused). I'm also really enjoying this hashtagging thing. Apparently it's pretty big with the kids these days. I guess all you do is put the # symbol in front of stuff and people think your witty. Seems easy enough. Anyway, you can follow me on instagram now as "hiredlens". And make sure to check in every Tuesday to see my new weekly addition to #tuesdaytaxidermy. Can you believe no one had used that already? Weird, huh? Enjoy.

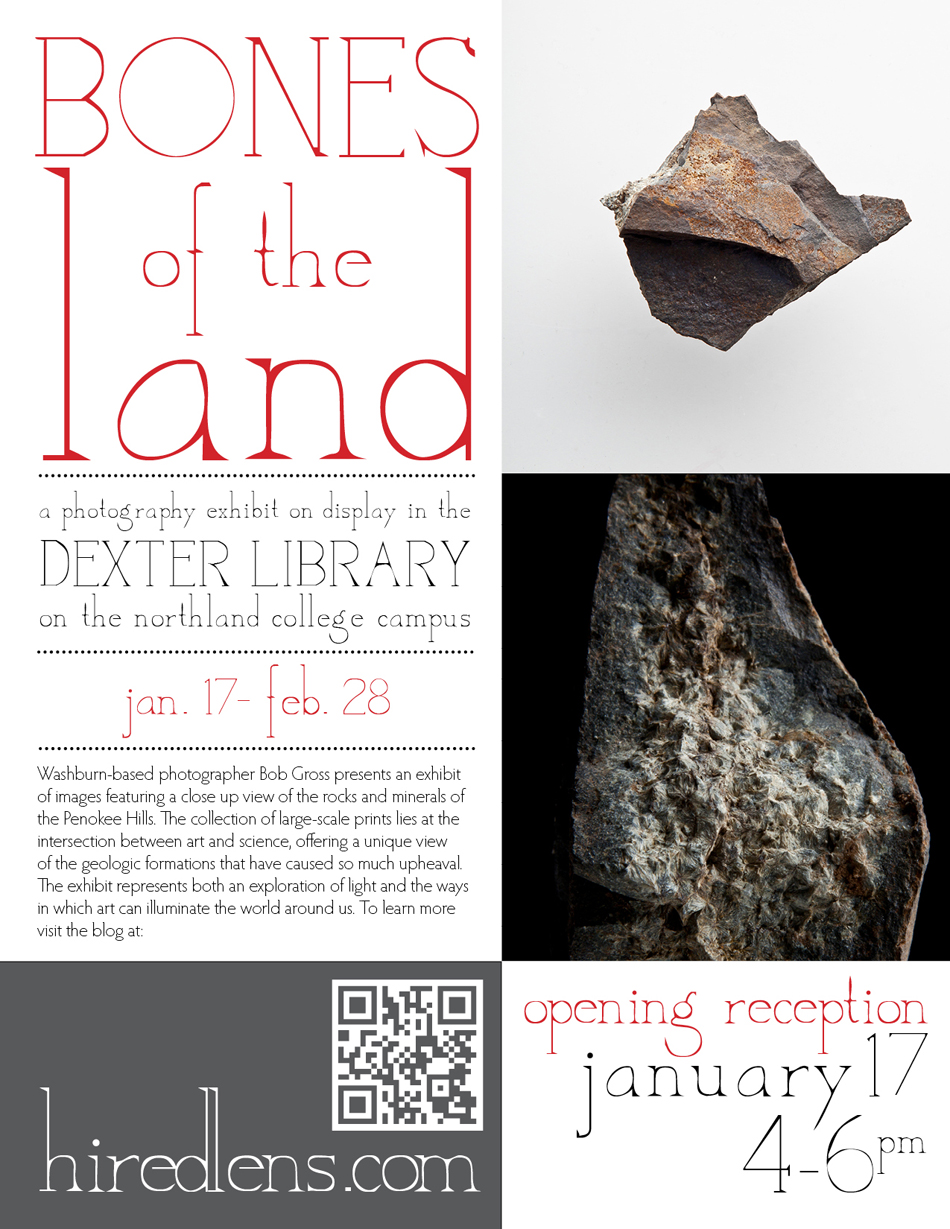

Bones of the Land on WPR

Bones of the Land has been getting some really great attention the last few weeks in the media including this awesome spot on WPR's Wisconsin Life. Special thanks to Daneille Kaeding and Tom Fitz for helping put this all together. You rock! Ha. Get it? Ha. And thanks to everyone who has come to see the show or checked it out online, I'm truly honored by all the support and kind words. Thank you.

Now I just need to find somewhere else to hang this show when it closes at Northland College in the end of February. Any ideas? Any other Wisconsin galleries interested? Give me a call.

Bones of the Land-Online Gallery

Can't make it all the way up to Ashland to see Bones of the Land in person? No worries. You can see it online right here. Or click on the images below to see a larger version of each print.

Bones of the Land-Reception Today!

Do you like art? Do you like science? Do you like when the two meet and at first it's kind of like an awkward middle school promenade where the boys and girls stand against opposite walls of the gym, but then the music builds and Art and Science come together in a magically beautiful breath-taking dance? Yeah, me too. I like it when that happens, too.

So, great. We'll see you this afternoon at 4 p.m. in the Dexter Library for the opening reception of Bones of the Land.

** PLEASE NOTE: There will not actually be any dancing. That was a metaphor. I'm sorry if it was misleading. There will probably be some cookies though. And you can stand by one of the walls and not talk to anyone if you want to. Totally your call. See you there.

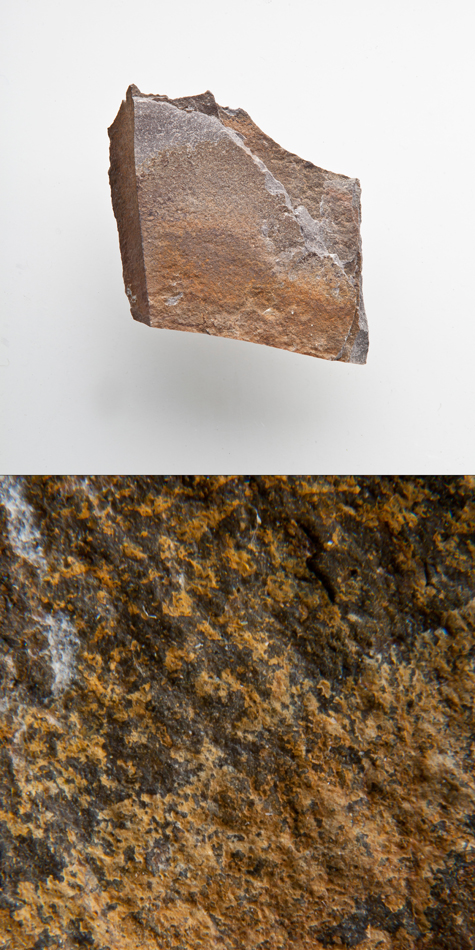

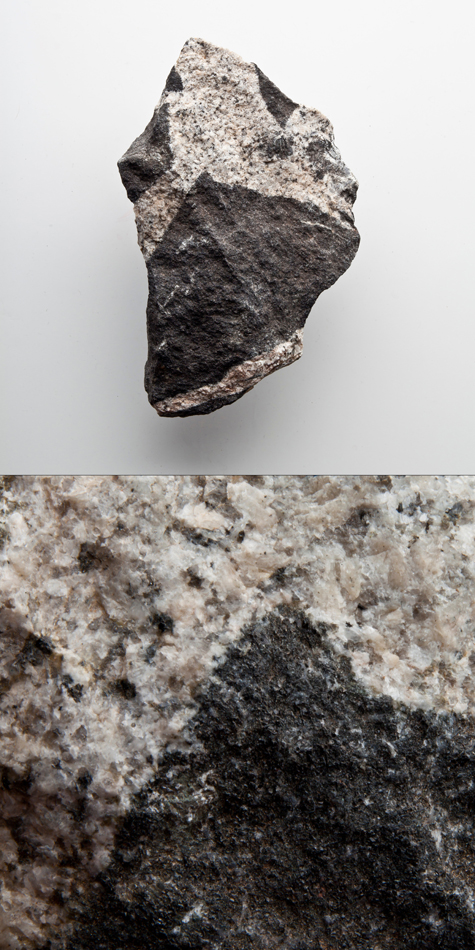

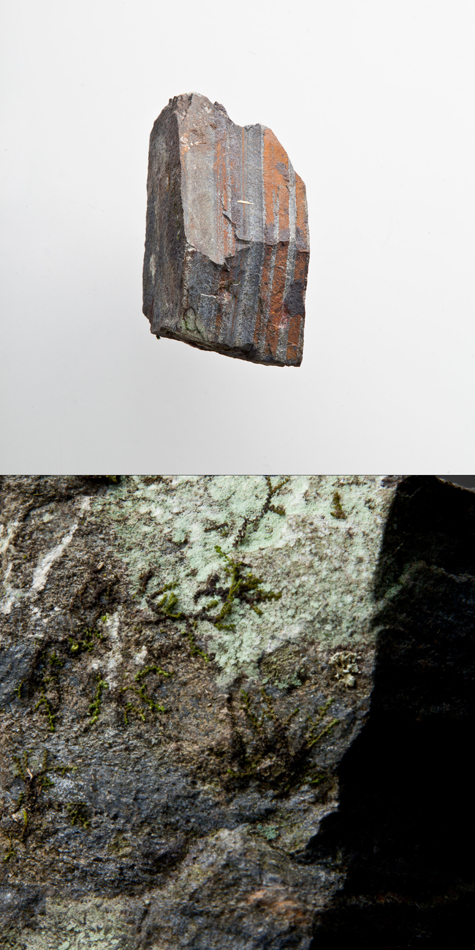

Bones of the Land-apparent size & macro photos

Light is the key to photography. And controlling that light to tell the story you want to tell is the key to making the images you want. For Bones of the Land I wanted to tell a story about something really small. Which meant I had to take the same lighting concepts that I use when I shoot big things like people and cars and angry bears, and apply them to something really small, like minerals. And that turned out to be way harder than I thought it would be.

For each diptych, the photo on white (like the one below) was shot by placing the rock sample on a piece of plexiglass suspended 2 inches above a white background and lighting from slightly above the plain of the plexi with one mono block firing into a 36x48 softbox. That created big soft even light across the whole sample and I could use the feathered edge of the light to control the slightly offset shadow and gradient that I wanted on the white below the rock. It took a little tinkering with each sample, but, all in all, pretty simple. (These photos were shot with a 70-200mm f/2.8L, mostly around f/20 handheld standing above the samples).

The second photo of each sample (like the one at the top of the page) was more difficult. Like, a lot more. And here's why: when I diagrammed my lighting concepts, it was based on the idea that I could put my light source anywhere in the hemisphere of space from the plain of the plexi up into open space. Which I could, but I forgot one thing: the camera. Which, as you may know, is kind of important. Critical, in fact. And shooting with a 5d MKII with a stacked 2x teleconverter, an extension tube, and a 16-35 f/2.8L or 70-200 f/2.8L on a ball head tripod perched over the sample, not small.

But regardless of the bulkiness of the camera setup, the real problem is all about apparent size. Apparent size? Okay. Say you're shooting a portrait of a person. You stand 10 feet away and even with the biggest, most ridiculous lens you can find, the camera blocks out only a tiny percentage of the hemisphere of space around that person. Its apparent size compared to the subject is relatively small. That leaves a huge range of options for where to place the light source. If your working with a large light source, you can even put the camera between the light and subject with minimal impact on the final image.

Next, try to photograph something from less than an inch away from the subject, and the camera now blocks out a massive portion of the hemisphere of available space. The exact same camera now has a huge apparent size. In fact, most of the angles from which you could light the subject are now eliminated because of the shadow cast by the camera and lens.

Still a little fuzzy on apparent size? Okay, here's an even simpler description. Hold your hand out at arms length. It takes up a tiny portion of your field of view, right? Now hold it one inch from tip of your nose. Now it takes up a huge part of your field of view. Same hand, different apparent size. Got it? Good.

This is a pretty basic photo concept (it applies to light sources too), but I'll be honest, the impact it would have on my lighting setup for this particular project didn't really occur to me until I looked at my first test shot for macro portion of the series. My work flow at that point went something like this: take photo > review photo > face palm > return to drawing board.

But after that trip back to the drawing board I came up with something that worked fairly well. I ended up putting the light source next the camera, very close at roughly a 90 degree angle to the lens axis, so that it could pitch light into the small gap between the end lens element and the sample. This would result in a fairly severe look for a portrait, but for the relatively flat surface of the samples it accentuated the texture of the surface. Then, by adding white reflectors on two sides very close to the sample (or perched on top of the larger samples, just outside the frame) I could lighten the stronger shadows cast by the very steep angle of the light. And there you go: directional light, controlled shadow, texture; all the stuff your looking for in a good macro image. All it took was a little trial and error.

**Don't forget to join us on Friday, January 17 from 4-6 pm in the Dexter Library on the Northland College campus for the opening reception of Bones of the Land. And stay tuned for more.

Bones of the Land.

It's been a bit of scramble this week, but this is all coming together. Here's the poster for my next exhibit, Bones of the Land, opening this coming Friday, January 17. Come check it out (there's reception from 4-6 p.m.), and stay tuned for another post later this week about how I shot the photos in this series. And watch for the new collection of cards with images from the show available in the our online gallery & store. In the meanwhile: keep it real out there, people.

Art theory and the selfie.

Big news this week. Earth shattering, even. The Oxford English Dictionary, a long-standing pillar of lingual excellence, has named seflie the word of the year. And then I cried. And here's why:

To those of us archaic enough to use whole words in dazzling combinations to describe the world around us, there was already an existing phrase for recording ones own image. It was called a self portrait. It's been a called a self portrait for centuries. We had that covered. But, apparently, once you supply millions of people with smart phones, it needs a new word. With fewer characters. And this brings me to my second point.

Paul McCartney did not invent the selfie. Neither did Kim Kardashian. Or Ashton Kutcher. In fact, the selfie has been around since...well, since art has been around. Though we can't be certain, a good argument could be made that the simple human form represented in the cave paintings at Lascaux is, in all likely-hood, a selfie. Maybe that's a stretch, but you see my point: it's not exactly new.

Great artists throughout history have created self portraits. So have a whole host of lesser artists. They litter the walls of galleries and museums the world over. And regardless of the medium used to create them, they were called self portraits. While the duck-face is an interesting new addition to the genre and may merit some choice words of it's own, an entirely new genre it does not make. Neither does the fact that people are using a smart phones or digital cameras to record their self portrait. They are still self portraits. Mostly badly planned and poorly executed self portraits, but self portraits none the less. Am I just being persnickety about this? Yes, probably. Okay, definitely yes, but I have my reasons.

The underlying implication is that digital art is somehow different than other media, less artistic in a way. And this bothers me. While it may be more prevalently used than say watercolor or sculpture, this does not make it less valid. Just because more people choose to be mediocre practitioners of the form should not denigrate the entire medium. If we all started making really bad oil paintings would we start to think less of Rembrandt and Vermeer? Would we start calling them "paintsies" instead of paintings? I hope not. But I'm less sure about that than I once was. It's important to recognize that it's not the tools that make the art, but rather the artist, good or bad, using those tools. Great digital art is still far more about concept and technique and delivery than the 1's and 0's that give it life.

None of this is to say that the Oxford English Dictionary is at fault. By reporting the 17,000% increase in the use of the word over the last year, OED is merely the messenger bringing us the tragic news of our own downward spiral. The one silver lining, I suppose, is that selfie beat out twerk for word of the year. But not by much. We're doomed.

This vaguely photography related rant was brought to you by caffeine and the letter S.

How I name files for optimal work flow.

And why no one should care...at all...ever.

I got an e-mail recently asking how I name files and organize folders to archive my photos. It's not the first time someone's asked about that, and as an avid reader of other photo blogs I've seen a lot of posts about similar things: Name your files to optimize work flow, what's the best program for photo sorting?, how to archive your photos. Some are helpful, most are not.

Over the years I've found good ways of doing things, and bad ways. I've improved my own process and habits to make my work flow more efficient. I've tried this and that. I'm a big believer in sharing information so when someone asks a questions, I'm happy to share what I do. If you really want to know how I number files in a project folder I can tell you. And you, in turn, can fall asleep and drool on your keyboard. That's fine, but to be honest, no one should care at all about how I or Joe McNally or Annie Liebovitz (do you like I how I lumped myself in with that group, pretty sweet huh? You get to do that when you have your own blog) name files. Ever. And here's why: it doesn't make the photos any better.

At the core of these questions (and a lot of other questions I get about photography) is the the underlying notion that there is a right and wrong way to do it. There is a way all the professionals do it and that's what makes them professionals. Let me reveal the big secret: there is no wrong way.

There is only what works for you. And what doesn't. Figure out the difference and stick with the first one. This applies to all kinds of things. Don't like carrying around all kinds of lighting equipment, get good at shooting ambient. Don't like processing images in photoshop, set your profiles to your style and shoot straight to JPG. Don't like telephoto lenses, shoot everything wide. Astounding images have been made in every way you can imagine, and probably some that you can't. Your file names are not your limiting factor.

Want to get better at photography? My best advice is to spend more time shooting the things that you love to shoot. Become obsessed. Then when you're famous, let your assistant figure out how to organize the files.

Bumps and babies.

Photography is awesome. I love it. And, over the past several years of working as a photographer, it's been pretty fun to see how the rest of your life can drive your career. Several years ago, when all of our friends were getting married, I shot a lot of weddings. A lot. And because I was posting a lot of wedding photos out on the old world wide webs, I got a lot more calls from people I didn't know about shooting weddings for them too. Business took off. Then I delved into cooking a lot more. Food and commercial work started to dominate my portfolio. And I got more calls about that. Then I started to play with lifestyle photography. And guess what I got calls about that too. You can see where I'm going with this.

Now, everyone's having babies. Like, everyone. Like, I think Sarah and I might be the only people in a tri-county area who are not currently pregnant. So naturally, I'm shooting a lot more maternity and baby photos, like these for our friends Katie and Dave. If the historic pattern holds true, I suspect I'll be getting more calls about these sorts of photos soon. And I'm ready for it.

Why? Because it's something new. If all I ever shot was weddings or food or whatever, it would get old. Stagnant. Boring, even. It's the change that keeps me excited about doing this everyday and keeps it challenging. So bring on the bumps and babies.

And what's after babies? Who knows. But I bet it'll be fun. Stay tuned to find out.

Solstice Outdoors.

We managed to sneak in one more late-summer photo shoot last week for our friends at Solstice Outdoors. Lucked out big time with the weather. After some fairly cold days, a few frosty nights, and one rain delay on this shoot, we ended up with a perfect blue-sky afternoon and some reasonably warm temperatures to be on (and for me, in) the water. This shoot definitely reminded me how much I love shooting outdoor sports. The movement, the colors, the scenery. It's hard not to enjoy. Plus, I get to do all kinds of fun stuff just to get myself to the locations. Gotta love that. Stay tuned for more.

Almost back on the map.

Looking for a good way to lose 5 months and spend all your money? Buy a house. We closed on our property April 1st (how's that for an auspicious date?) and went straight into "put your head down and work" mode to get it ready to live in. I finally looked up last week and was shocked to find that the summer was over. Over. It disappeared in puff of of sawdust and a swirl of bent nails. Now, I don't mean to complain. We've been lucky enough to have a ton of help from friends and family all along the way and the house is looking pretty incredible. But still...Holy #$%&. What happened to summer? It's just...gone. And I hardly made any photos. That's the worst part.

On the up side, the end is in sight. I'm not saying the house is done. It's not. Maybe it never will be. But it's done enough that we can give up for a while, and do something else. And that means I'm getting back to doing more photo work in the next month. I've got a handful of shoots scheduled already and more in the works. Keep your eyes peeled for some new work. I'm almost back on the map.